Reflections on the Collection

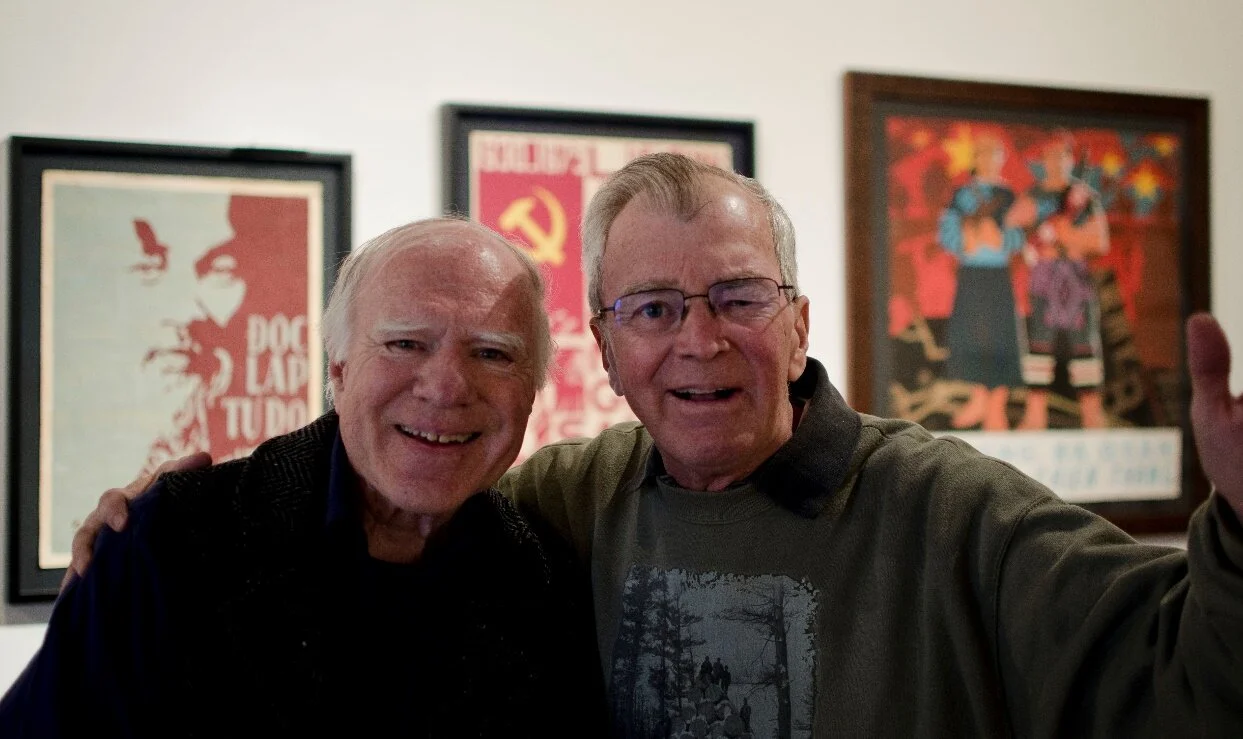

I am so very grateful to be able to share with everyone this collection of Vietnamese art that my long term friend Bruce Blowitz left me following his untimely death in July 2015.

Bruce was a very feisty and fun loving guy who enjoyed travel as much as I did. As soon as I came to Bard College in the fall of 1968, my friends insisted I meet the “other guy” from Chicago when he returned to school after taking a semester off. Bruce found me again in Amsterdam in the spring of 1971; so began the first of weeks of travel which in later years found us together in the western states of America, Nepal, and Southeast Asia.

Bruce first visited Thailand in the 1970s as a tourist, but he soon took a degree at the Gemological Institute there and became a dealer in precious stones. This had him traveling often to Southeast Asia.

When Vietnam was opened to American tourists in 1992, Bruce and I made our first trip to Hanoi together. In 2000 Bruce moved to Phnom Penh, Cambodia after selling his investments in America to pursue his new love of art and art collecting.

Historically, civilization first began in the area around the Red River, many of thousands of years ago, near to what became Hanoi. The country continually had to defend itself against Chinese, British, and Dutch colonial interests before being taken over by the French in the 19th century. The French established an art academy, L’École des Beaux-Arts de L’Indochine, in 1925. This school was the defining moment for many of the famous artists from Vietnam. After the communist government came to power, the art school directed the artists to paint pleasant pictures of the people at work in the factory or in the villages. They were also given the task of helping with war propaganda, examples of which are in this exhibition.

Note that the work is done with very limited resources. Artists had very few pieces of canvas and their paint was made using whatever materials they could find.

While the United States was fighting to stop communism, the Vietnamese were fighting a civil war, or as they called it, the War of Unification. Today, Vietnam is a developing country with new construction, and private enterprise. My hope is that, through this exhibition, you will enjoy a more comprehensive understanding of the Vietnamese and their history, and that someday a friendship similar to what we share with Japan and Germany will be true.

– Albert I. Goodman

From the Artistic Director

The John David Mooney Foundation is honored and delighted to host this collection of paintings recently acquired by Albert Goodman. Three reasons stand out as to why this exhibition of Vietnamese Art is of distinct significance.

First, it is a snapshot into the cultural milieu of Vietnam as far back as sixty years ago, viewing through the paintings, the aspirations of the artists and those of their patrons. This aspect of life in Vietnam, and the stories they reveal, were not recorded nor transmitted back to America. Wartime journalists focused on the body count.

Second, is the discovery of an artist of merit, Bùi Xuân Phái, who pursued his own vision instead of following the demands of Hanoi. These paintings by Phai, devoid of any propagandistic message, are presented here as a one man show within a show.

And, the third and most important reason, is the dedication and commitment of Albert Goodman to honor the memory of his close friend, Bruce Blowitz, also a Chicago native, and to fulfil Bruce’s wish that the work he collected be properly shown and made available to the public.

The International Currents Gallery of the John David Mooney Foundation which showcases only international art and artists, fulfills this request. The value of friendship and its importance is a pillar of the John David Mooney Foundation. We are most pleased that friendship is at the core of this exhibition.

– John David Mooney

“Vietnam as seen through Vietnamese Artists’ Eyes”

- by journalist Alison True

Post-War Vietnamese Art

from the Albert I. Goodman Collection

This exhibition is a display of works that belonged to an American who, prior to his death in 2015, lived in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Before he died, he willed his collection to his longtime friend Albert Goodman, trusting that Albert would show it to a public in America. Bruce Blowitz was very fortunate to have acquired masterpieces by the first generation of Vietnamese modern artists, many of whom graduated from the national colonial-period art school and then survived revolution and poverty when the country was divided by politics and foreign occupation.

Bruce began buying art there when Vietnam was just opening up to foreign tourism after a decades-long closed border to tourists, and this exhibition showcases the highlights of his collection, which include some of the most important artists in modern Vietnamese history.

Vietnamese art historians generally credit the advent of modern art in the country to the establishment of the first art academy there in 1925, by the French painter Victor Tardieu (1870-1937) and the Vietnamese artist trained in France, Nguyen Nam Son (1890-1973). The Ecole des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine based its curriculum partly based on the Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Paris and combined classes in local art forms such as lacquer and silk painting with lessons in oil, portraiture, life drawing, and still life. After the school moved further north in 1945, to the seat of the resistance movement, artists began making naturalistic paintings of their countrymen to promote the spirit of nationalism. When the country split into two political halves in 1954, the Republic of Vietnam in the south and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north, the artists who ended up in Saigon continued in the tradition of landscape painting, with idyllic scenes of the countryside. But the artists in the north were recruited to return to Hanoi to help promote communism, and while some embraced the state ideology wholeheartedly, others advocated for more freedom of expression and the creation of art for its own sake. Some of them refused to join state-sponsored exhibitions and artists’ unions and were therefore ignored by official arbiters of taste.

But after the period of economic renovation in the mid-1980s, under the policy known as Doi Moi, and bans on certain styles and techniques were lifted in 1991, artists gradually began to work publicly in forms such as nudity and abstraction. Many of the works in Bruce’s collection date to the early 1990s, when work by seminal artists was readily available. At that time, it was possible to meet artists in cafes, and without galleries or middlemen, visit their homes and buy work from them directly or from friends and colleagues of the modern masters who had saved their works. The works in this exhibition were produced by artists who had no access to modern technology or international art movements, but who worked in a time and place rich with historical and political significance. They also reflect a time in Vietnam when art was an important part of everyday life and modernism was a major influence on it.

– Dr. Nora A. Taylor

Alsdorf Professor of South and Southeast Asian Art

School of the Art Institute of Chicago